This sounds grim because it is grim; our season runs from November through to March and we’re on the tops in the worst conditions Yorkshire has to offer. At the end of a long day in horizontal rain, following survey transects to record erosion features, peat depths and vegetation communities, there’s enormous satisfaction, pride even, in having endured that to achieve something that matters. We’re tackling climate change, we’re mitigating flooding downstream, we’re helping to keep our reservoirs clean and, most importantly, we’re giving Yorkshire’s glowering moorlands a second chance at wuthering glory. We’ve been at it for 15 years now and we wouldn’t be anywhere else in the world.

Over the last decade and a half, the programme’s numbers have grown so that their enormity is almost mind-numbing. Since 2009, we have brought 46,952 ha of peatland into restoration management, which is 50% of the estimated 94,220 ha of peatland in our operational area. To achieve this, we have:

- Secured £6.5 million to cover core costs (e.g. staff, vehicles, equipment and office costs)

- Secured £30 million of capital funds to carry out direct peatland restoration

- Completed foot surveys of 70,825ha of peatland

- Completed restoration plans for 67,623 ha of peatland

- Planted 3.8 million plug plants, including 2 million sphagnum plugs

- Blocked almost 3,000 km of gulleys and drainage ditches

- by installing 253,000 sediment traps (dams) to slow the flow of water on the fells

One morning in March, 2019, saw me planting crowberry plugs in conditions you can only really understand if you’ve spent winter on Fleet Moss (March is still winter on Fleet Moss). I think I planted 500. My back was ruined and my fingers were stiff for days. The idea of planting 3.8 million plugs crushes any attempt at comprehension. Between 2009 and 2019, we only(?) planted 218,000 plugs. How did we get from circa 22,000 plugs a year to a total of 3.8 million in only 15 years? I’m glad you asked…

Planting cottongrass © Jenny Sharman

Me, crouched in the bitter wind, planting cottongrass and pondering the life choices that had led me to this moment...

Safety blanket

Back in the mid-noughties, people started to catch on to both the importance of our blanket bogs and also just how badly damaged they had become. Agricultural policy following World War II had led to drainage in pursuit of agricultural improvement. As water tables dropped bog surfaces dried out, killing off the characteristic flora that makes bogs bogs. Shorn of its protective vegetation overcoat, upland peat was exposed to the erosive effects of the weather and either washed off into river catchments below or simply billowed away into the atmosphere.

At the same time, there was a gradual pushback against the lifeless-wasteland narrative that had dogged these amazing places since at least Wuthering Heights (1847), and we began to recognise Conan Doyle’s great Grimpen Mire for the fiction it is. Far from being scenes of horror, they support and nurture us – a safety blanket (bog), if you will. Upland peatlands store carbon, filter our drinking water, mitigate flooding downstream and provide space for recreation, but we diminish them when we frame them solely in the context of the benefits they afford us.

Blanket bog at Fleet Moss © Lizzie Shepherd

Far more than just services

These magnificent, brooding landscapes may appear forbidding and solemn if you experience them in bad weather (as we generally do). Catch them on a sunny day, though, in late spring or early summer when the bubbling call of the curlew – somehow joyous and haunting – is ringing out across the moor; underfoot, a thick, rolling carpet of sphagnum hummocks blankets the ground in shades of green, yellow and red; soft, white heads of cottongrass bob luminously in the gentle breeze; a dragonfly circles a pool, its glittering wings rattling; cranberry, bilberry, crowberry, cloudberry speckle the moss, tiny jewels; overhead, a skylark rises into the sky to parachute back down like a musical shuttlecock; on the horizon, a short-eared owl quarters the ground on elegant, sculling wingbeats. Whatever services our peatlands provide, they are first and foremost homes for wildlife and they are beautiful.

Sphagnum squarrosum - spiky bog moss © Beth Thomas

How it started

Back in 2008 peatland restoration work was already underway in the Peak District and South Pennines (under the Moors for the Future Partnership) and in the North Pennines (under the North Pennines Landscape Partnership). However, this left a big gap running through northern Yorkshire. In response, a consortium of stakeholders funded by Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority (YDNPA) and Yorkshire Wildlife Trust (YWT) commissioned Tim Thom (YDNPA) and Astrid Hanlon (YWT) to scope out the potential for a peatland restoration project across northern Yorkshire. This scoping assessment led to the creation of Yorkshire Peat Partnership in 2009, now hosted and led by Yorkshire Wildlife Trust.

Fleet Moss in 2018 © Jenny Sharman

How it’s going

The importance of peatlands and their restoration has risen on the agenda since 2009. Whilst we can’t say that restoration funding is easy to come by, it’s no longer a case of purely finding the right option on an agri-environment scheme. In the public sector, specific funding pots such as Nature for Climate (NfC) are now available, and charitable trusts such as Garfield Weston Foundation and Esmée Fairbairn Foundation have provided essential support for our core funding as well as restoration. You can find a full list of our funders in our annual report.

Fleet Moss in 2024 © Jenny Sharman

Policy and funding recognition

With the rising profile of peatlands has come a recognition of the scale of the damage, the need to redress that and a concomitant rise in the availability and flexibility of funding.

In May, 2021, Defra published the England Peat Action Plan (EPA), with this foreword from then Secretary of State for the Environment, George Eustace:

“Our peatlands are an iconic feature of England’s landscape. Often referred to as ‘our national rainforest’, they perform many functions – they are our largest terrestrial carbon store, a haven for rare wildlife, a record of our past, and natural providers of water regulation. Yet, for too long we have taken this valuable natural resource for granted. Only 13% of England’s peatlands are in a near natural state.”

The EPA also heralded NfC, a very welcome change to the way some previous funding streams were managed. A major stumbling block in the early stages of the project related to the system of paying for works and claiming back from Natural England under the Higher Level Scheme. Under the scheme, 100% grant funded works such as peatland restoration required agreement holders to pay up front and then obtain a “receipted invoice” in order to submit a claim to Natural England. Given the high cost of peatland restoration and the size of invoices most landowners were reluctant to pay out such large amounts and then wait for an unspecified period of time while their claim was processed.

In contrast, NfC gives peatland restoration partnerships the ability to apply directly for funding with no administrative or financial burden for the landowner; this means that our interventions are not limited by what an agri-environment agreement holder can afford to bankroll. Another very helpful development is that this funding stream will also pay for staff to carry out the restoration works. Although agri-environment schemes funded capital works, without staff to conduct surveys and write restoration plans, those works took a long time to come to fruition. We hope that the scheme will be extended while the new administration comes to conclusions about the successor to the current Countryside Stewardship scheme, Environmental Land Management schemes.

Measuring out an NfC monitoring plot in Langstrothdale © Beth Thomas

Monitoring, research, and technology

It’s not just the nuts and bolts of restoration to which NfC is making a difference. In the infancy of our work, another function that we could not get funded was monitoring – this made it difficult to state with absolute certainty how much difference our interventions were making and over what timeframe. Certainly, we could look and see that vegetation was returning and the bog was more squelchy but scientifically speaking, this is anecdotal. We now have funding – for both equipment and staff – to conduct baseline studies before works commence and across the restoration programme

We have also been looking at new ways to achieve results more efficiently. We have slowed the flow of water across bare peat with coir logs; imported cell-bunding from lowland restoration to cost-effectively control water on shallow slopes; taken to the skies with Unoccupied Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to better understand how water moves across the landscape and so target our interventions more accurately. Where once we used paper maps and dead reckoning to map erosion features, we now input peat-depths, erosion features and vegetation records onto handheld GPS mappers; the data is downloaded to our open-source database, BogBase, which can automatically produce a restoration plan.

Quadcopter unmanned aerial vehicle © Dave Higgins

Building capacity

As the aspirations of the team has grown, so has the team itself, from a handful in 2009 to almost 30 in 2024. In our first 5 years, we worked on circa 21,000 ha of peatland, roughly 4,200 ha per year; this season we worked on 7,300 ha. The sector’s aspirations as a whole are also growing but they are outstripping capacity. Across the country, as the urgency of restoration has increased, the number of people able to carry it out has remained static. To address this shortfall, we have designed a LANTRA accredited course, now in its third year. It is open to learners from across the UK to give them the skills and know-how to implement effective restoration best-practice and enables them to make a real impact on the ground. This course is for:

- Those looking to develop skills in project managing peatland restoration, from survey to construction

- Those looking to gain accreditation to support professionalisation of skills

- Those looking to gain understanding to enter the peatland restoration sector

Additionally, we began running a 2-day introductory course this year, aimed at those who need to understand the basics of the sector before committing to self-development for it.

Peatland practitioner students receiving training in the Yorkshire Dales © Tess Levens

Building community

We want people to care about our peatlands and take action to help us rewet, replant, restore. In 2022, we stepped beyond standard communication into engagement with our Give Peat a Chance exhibition at the Dales Countryside Museum and then the Museum of North Craven Life in Settle, and finally in Cliffe Castle Museum in Keighley. We sought to inform and engage the public about peatlands through the lens of artistic interpretation, using visual arts, textiles, film, poetry and music, all centred around a bog in a box.

Building on this, we are seeking to expand that engagement with our ACE Bogs project with Denton Reserve in Nidderdale National Landscape. At the heart of ACE Bogs is the aim to engage the public in understanding the management of peatlands through active volunteering and involvement in a long-term citizen science project. ACE Bogs intends to equip volunteers with the skills to monitor key indicators of the health of peatlands over time. As well as this, the project aims to provide opportunities to volunteers to use what they have learned and observed to share their findings and analysis with others through a series of artist-led workshops to generate and disseminate creative campaign outputs.

Our monitoring work is also a keystone of our engagement activities, both through NfC funding and the IUCN UK Peatland Programme’s Eyes on the Bog. It enables our volunteers not only to feel that they are making a difference but also act as advocates for peatlands and their restoration.

ACE Bogs poetry workshop on Bog Day 2024 © Lucy Lee

On the virtual side of engagement, we have a catalogue of peatland films on our Vimeo channel, produced in-house, to entertain and educate. We have expanded our social media channels from Twitter (nobody really calls it X) to include Instagram and TikTok, with some fairly rapid successes:

- Followers: 07/2023 – 119 followers, 07/2024 – 588 followers

Tiktok

- Followers: 07/2023 – 56 followers, 07/2024 – 2,213 followers

- Total likes: 07/2023 – 613 likes, 07/2024 – 108,622 likes

- Most liked video: 07/2023 – 326 likes, 07/2024 – 42,000 likes

- Most viewed video: 07/2023 – 3,402 views, 07/2024 – 453,300 views

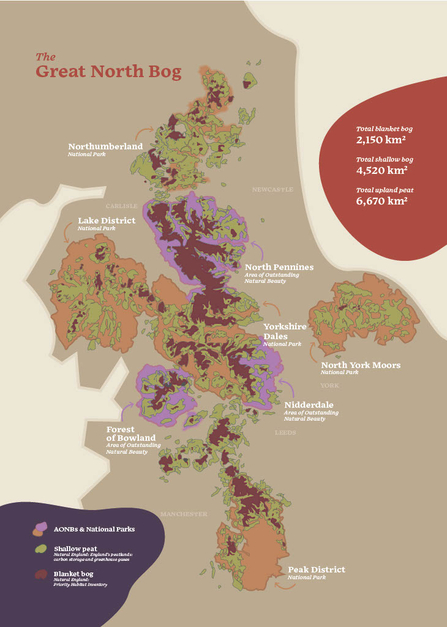

Great North Bog

It is YPP’s pioneering spirit that we hope to share with our partners in the Great North Bog, spanning 7,000 sq km of peatlands across the north of England. Our 15 years of graft and earned expertise can not only help those that have recently come into our niche, it can demonstrate to private finance that this coalition is worthy of their investment.

Map of the Great North Bog

You can read about the last 15 years in our new report and about about out last season in our 2023/2024 annual report.