Bog pool on Fleet Moss © Lizzie Shepherd

Our peatlands

We estimate that northern Yorkshire’s peatlands currently store 27,410,845 tonnes of carbon*.

Blanket bog above Raydale © Lizzie Shepherd

In Yorkshire

Our operational area contains 92,946 ha hectares of blanket bog, of which the majority is damaged. 27% of England’s blanket bog is in North Yorkshire, making this a landscape deserving of protection.

Our story

Vegetation recolonising peat behind and between coir bunds © Jenny Sharman.

Yorkshire Peat Partnership began in 2009 as an umbrella organisation to try to coordinate the restoration of the badly degraded peatlands in the uplands of northern Yorkshire. Since 2009, YPP has developed into the primary organisation coordinating the delivery of upland peatland restoration across the Yorkshire Dales and North York Moors National Parks and Nidderdale National Landscape.

Our progress

Drainage channels - grips - ploughed into moorland to lower the water table © YPP

As at March, 2023, we have brought 42,868 ha of blanket bog into restoration management. We have blocked 2,632 km of eroding grips and gullies, reprofiled 3,915 km of hagging, and planted 1.3 million sphagnum plugs and 800,000 cottongrass plugs, and revegetated 209 ha of bare peat.

Walkers © Watershed Landscape

Public benefits

Yorkshire's peatlands provide many benefits; some you experience directly yourself and some are harder to appreciate (but just as important).

Public benefits

Climate

Weather station © Matthew Snelling

Peat is formed by dead vegetation that is unable to fully decompose in the waterlogged environment. Because the plants' decomposition is incomplete, their carbon is not released into the atmosphere; it is instead locked up in peat. Globally, peatlands are the largest terrestrial store of carbon. The carbon stored in peat is estimated to be twice that found in forests.

Flooding

Flooded road © Tessa Levens

Flooding has been a significant problem across Yorkshire, with the Environment Agency spending £24 million in damage repairs in 2015/16. The real cost is, however, estimated to be much higher. Man-made drains (grips) cause water to run off upland catchments quickly, which can put populated areas at risk in times of heavy rainfall. Blocking these grips and restoring blanket bog vegetation can ‘slow the flow’ to keep these important habitats wet and limit flooding further down the river catchment.

Recreation

Family recreation © Watershed Landscape

Blanket bogs are fantastic places to visit. You can enjoy exercise, fresh air and tranquility in stunning landscape and, with luck, see some unique wildlife.

Economy

Kettlewell village shop © Lyndon Marquis

Not only are peatlands a fantastic place for people and wildlife, they have a very important economic impact on the region. The ability to limit flooding in heavily populated regions could prevent £millions in damage repairs.

Functioning peatlands also reduce the amount water companies have to spend to clean contaminants. This reduced production cost could result in cheaper bills for customers like us.

Millions of people in the UK spend their leisure time in green/blue spaces. The main reasons to visit these places are the habitats and wildlife that can be found. This in turn, supports a range of local businesses including nature tourism, that may otherwise become isolated. Without intact habitats offering diverse experiences, people would not visit these rural locations.

Erosion features

Grips

Grip running across open moorland © Tessa Levens

Most peatlands are criss-crossed with drainage channels known as grips. These take the water off quickly and were previously encouraged by Government, in a failed attempt to make the land more productive.

Gullies

Gullying around grips on Fleet Moss © YPP

Once the landscape is drying out, the vegetation dies, exposing the peat to erosion by the weather. This can lead to the formation of gullies - eroded channels carrying water and sediment off the bog, further driving a circle of erosion.

Hags

Hagging in a gully side © Rosie Snowden

Hags (or hagging) can occur in gullies, grips or on patches of bare peat. A hag is a steep bank of bare peat on which the angle of the slope - usually over 30° - makes it impossible for vegetation to re-establish. Once hagging has occurred, it will only get worse unless we take action to restore it.

Bare peat

Bare peat ©

Bare peat generally forms on gentle slopes or flat areas. Once the vegetation dies off, it is scoured away by the weather, exposing the peat to further erosion and driving the formation of gullies and hags. Bare peat allows rainfall to rush across the surface of the bog, both making it harder for vegetation to re-establish and driving flooding further downstream.

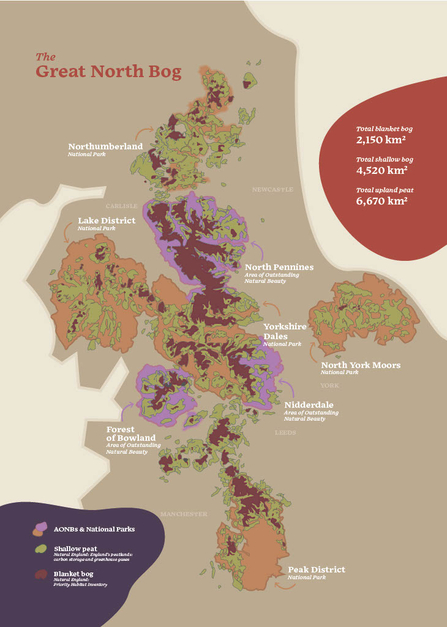

The Great North Bog

The Great North Bog is an ambitious, large-scale peatland restoration initiative being developed by the North Pennines National Landscape Partnership, the Yorkshire Peat Partnership and the Moors for the Future Partnership, together with the Northumberland Peat Partnership, Cumbria Peat Partnership and Lancashire Peat Partnership.

The Great North Bog is a landscape-scale approach to upland peatland restoration and conservation across nearly 7000 square kilometres of peatland soils in the Protected Landscapes of northern England, storing 400million tonnes of carbon. The programme aims to develop a working partnership to deliver a 10-year funding, restoration and conservation plan to make a significant contribution to the UK’s climate and carbon sequestration targets.

Map of the Great North Bog

*as at March 2023